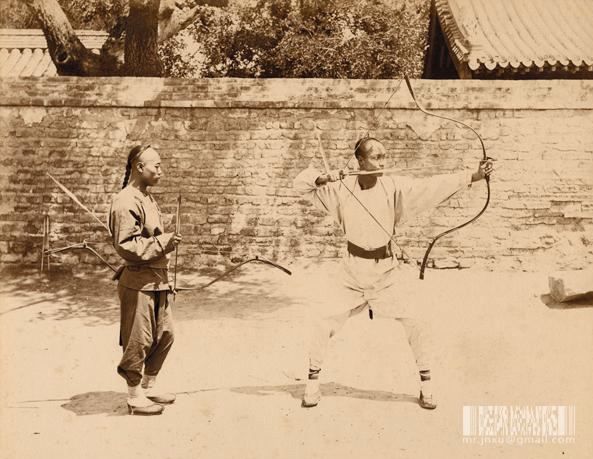

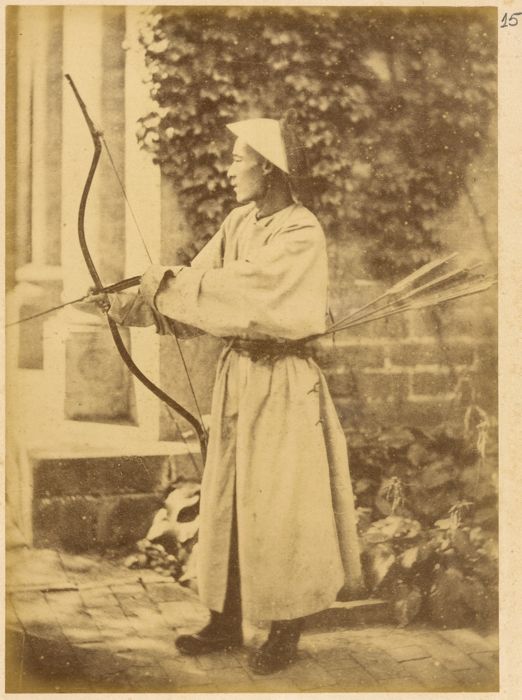

1.) Photo by John Thomson, Beijing, 1872

Peter Dekker:

The archer in full draw represents a classic example of the Manchu style. The other archer also seems to be knowing what he is doing, and is depicted in an early stage of the arrow loading process, which is a formalized sequence.

Justin Ma:

Maybe it's just an illusion caused by camera angle, but the foot placement is interesting because it looks kind of like the closed stance that some English archers like to use.

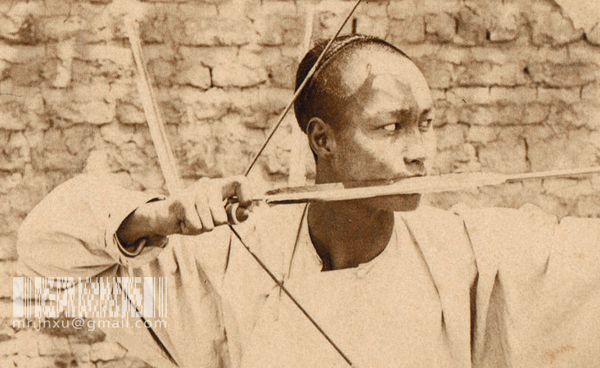

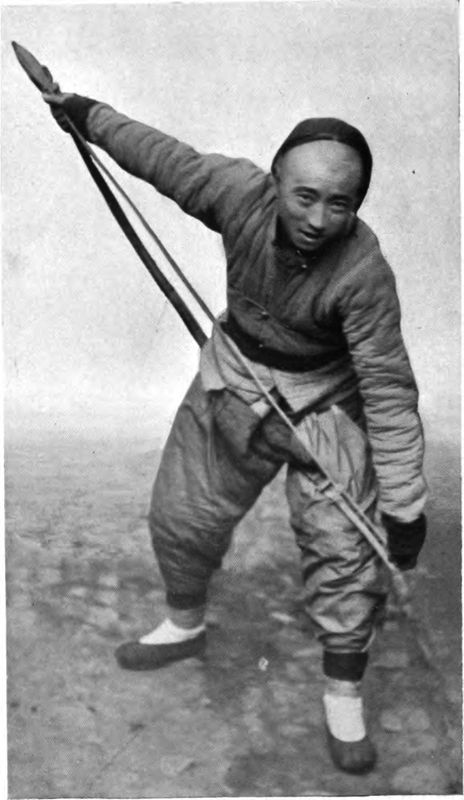

2.) Photo by Major Firmin Laribe of France, 1900-1910.

Peter Dekker:

An image showing a number of what appear to be juvenile archers being tutored by the elderly man on the left. There is a striking similarity with the equipment and poses of the previous picture, confirming that the "waiting stance" was a regulated stance that represents part of the loading and drawing sequence. It is also interesting to note the difference between the archers in full draw on both pictures. The top archer is fully settled in the classic Manchu stance, while the one below quite resembles contemporary beginners in the style, not leaning into the shot as much and with legs more spread.

Justin Ma:

The draw elbow is inline with the arrow, and the shoulder position is accepable. The reason he's not leaning towards the bow so much is because he's aiming upward. I can't quite tell what he's trying to do with his bow hand, but his bow hand's thumb is showing a lot of tension.

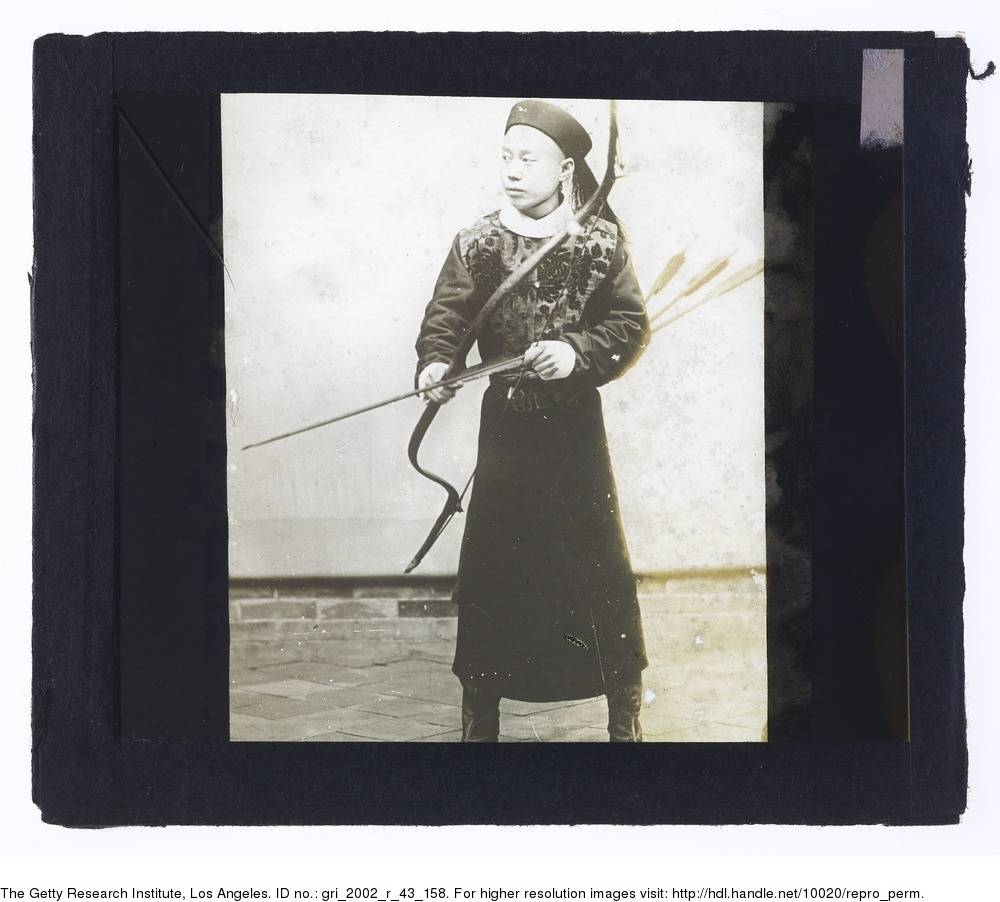

3.) From the album of an unknown American Diplomat, 1880 to early 1890's.

Peter Dekker:

This magnificent photograph shows a Manchu archer in a slightly later phase of the sequence than the left archer in picture 1. This archer is grasping his arrow behind the head with the index finger of the bow hand, while he strokes the feathers on his way to the nock. By feeling the feathers, he knows where the nock is so he can align it to the string without looking. Judging from the round dragon patches on his robe, this archer is probably of high noble rank. Manchu nobility was often well-trained in their classical fighting arts because they were supposed to serve as an example.

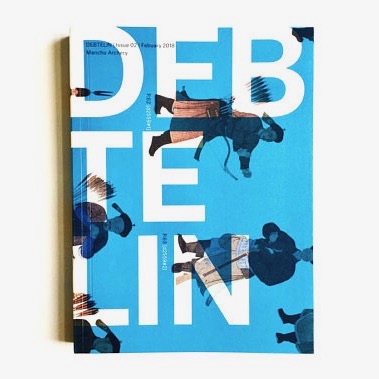

4.) Anonymous, ca. 1870. Throckmorton Fine Arts, New York.

Peter Dekker:

A group of archers. The archer on the left is holding what seems to be a heavy strength bow. The archer on the right is clearly posing for the shot, checking the camera man as reached full draw. Behind them is a rectangular board with three dots, such targets were used in the military examinations.

5.) Photo by Auguste Francois, ca 1870. Depicting Su Yuanchun, (1844-1908) a Manchu general in Guangxi.

Peter Dekker:

A high ranked military Manchu in full traditional garb. A tough illiterate Manchu, Su Yuanchun was one of the last great warrior Manchus. He gained merit in the field and made it from a simple soldier to a distinguished general. Quite a feat in a time when the Qing fought battles against modern firearms with sabers, spears, bows, arrows and matchlock muskets. He commanded a force against the French at the battle of Zhennan Pass, which despite the technological advantage of the French was won by the Chinese side. Su Yuanchun became a friend of consul Francois Auguste who was one of the first to ever make films of what he saw in China.

6.) Photo by Herbert G. Ponting, 1902. For stereoview publishing company C.H. Graves.

Peter Dekker:

This archer seems to be practicing the classical Manchu style as well, although I tend not to consider this picture the best example of the style. He seems to be putting a little pressure to the bottom of the nock, somewhat lifting his arrowhead up from the hand, something that is seen on Mongolian footage from the mid. 20th century as well. Before the shot, they would let the arrowhead fall into place. He appears to be standing straight with a straight bow, but from the wrinkles in his clothes and the difference between sizes of the ears of the bow we can determine that he is in fact leaning into the shot, as was the classic Manchu way of doing it.

Justin Ma:

For sure this guy is inclining forward at the hips (he is not keeping his trunk upright and bending at the knees). You can tell by the wrinkles in the clothing at the hips as well as the lack of wrinkles in the clothing at the legs. This is quite similar to the clothing wrinkle patterns you see in (7) and (8), for which it's more obvious that the archer in inclining forward a bit.

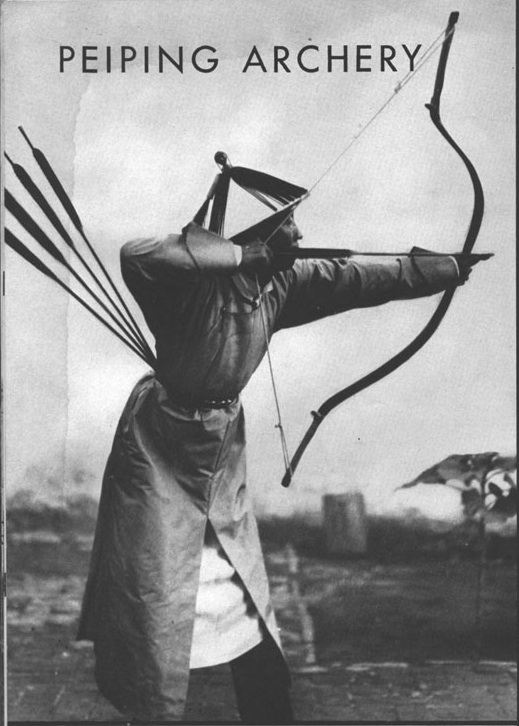

7.) H.R. Kress, probably late Qing. Published in Asia Magazine, New York, September 1936, with the following text:

In a narrow lane in Peiping are a few old shops with bows; here are the last bow-makers, all that are left of an ancient and distinguished profession of China. For archery was not only an accomplishment of soldiers, but a recognized recreation among scholars, and was practiced by Confucius himself. Today it survives as a sport and exercise, and in old forms of classic rites and ceremonies. The Chinese bow is made on a skeleton piece of bamboo about five feet long. At each end is an angled wooden spike, and in the center is first glued a piece of wood a foot long, over which layers of sinew are then laid. On the outside of the bow are two stripes of polished buffalo horn. Special test bows, of eight to twelve "strengths," were used in the military examinations of ancient times - "one strength" being equivalent to the lifting of thirteen pounds. (That would make 104 to 156 pounds of draw.)

Peter Dekker:

This, to me, is poetry! Together with the John Thompson picture at the beginning of the page this is one of the best examples of the classic Manchu style we have on record. He really seems to have it all down, a most graceful sight, his body in perfect equilibrium. It's our luck that there are two more pictures of this man in circulation. We can clearly see they are taken in the same place, of the same archer by the matching floor and matching wrinkles in his clothes.

Justin Ma:

The archer is not at full draw yet. You can tell by the lack of contact between the string and his clothes. [Peter:] Yes indeed. Also from the higher draw hand elbow and the fact that there is an angle between draw-hand wrist and hand that the archer doesn't have anymore in full draw.

8.) By H.R. Kress, from www.atarn.org

Peter Dekker: Full draw, taken from the side.

Justin Ma: Looks pretty good here: relaxed and in control. The elbow is not dropping down too severely here. Actually, the arrow is aiming up a bit, and he's keeping the top of his draw wrist flat. That makes the arrow almost inline with the top line of the elbow.

9.) By H.R. Kress, from www.atarn.org

Peter Dekker: Follow through. See how the bow does not turn in the handle like some of the fancier Chinese methods. Note that unlike Ku Ku's photograph and Liu Qi's manual where the palm ends facing backwards, this man's palm faces up after release. Such differences between schools of Manchu archers are for the most part only stylistic, and don't necessarily affect the shot with a proper release.

10.) Unknown photographer, Beijing, 1899.

Peter Dekker:

Although the Manchus were rulers of the Qing dynasty, not all archery practiced in this period was of the Manchu style. This picture is a good example of such a style that clearly deviates from the standard Manchu teachings. It seems that we are looking at Chinese martial artists practicing archery in their own style, incorporating the characteristic Chinese horse-stance in their practice. Other deviations from the Manchu style are the really long draw and straight back. On top of that, their dress is not Manchu, as Manchus were required by law to wear a winter or summer hat depending on the season. It is a clear example of the fact that Chinese archery styles endured, even though all Chinese archers did adopt the Manchu style bow.

Justin Ma:

The low-wrist grip is pretty atypical.

10a.) Detail of the archer's hand.

11.) Photo by John Thomsom, ca. 1865. From Stephen Selby's www.atarn.org

Peter Dekker:

The picture is most likely posed the archer seems to use an alternative grip in order to hold the bow long enough for the shot. With the technology John Thomson had available the exposure time would be seconds in summer, but much longer in winter due to the delayed effect of the chemicals at work. The archer wears a winter hat, and northern China can be very cold, so let's give him a break here. In any case, both his bow and string hand are not how they are supposed to be. The overall posture seems to be correct though, so the man may have actually known how to shoot these bows. Also note the size of the bow compared to the archer.

12.) Photo by Michel de Maynard, probably between 1906-1911. Treated in Ben Judkins' article on chinesemartialstudies.com. Also check out the full album in the Getty Research Institute Digital Collections.

Peter Dekker:

A Manchu nobleman about to draw his bow. Although he hasn't quite begun the real routine yet it seems to me that he is about to set into the classic Manchu archery style. He comes across as someone who knows what he is about to do. Certainly not a simple posed picture by a non-archer. Also notice how tight his belt is, similar as on the Kress photographs above. In copying this I found it helps spread the arrows out in a fan, but I also found it beneficial for my concentration and posture. Note that the photograph has been mirrored, you can tell from the clothing.

13.) Unknown photographer. Found on archerylibrary.com. They sent me this higher resolution image and gave kind permission to use it on this website. It was originally published in the article STRINGING THE CHINESE BOW by M.B. From the The Archer's Register for 1904-1905, pp. 279, Edited by H. Walrond, and came with the text:

"The most difficult and capricious instrument of Archery is the Chinese Bow, the largest of the Central Asiatic type, and big brother of the Turkish Bow, which is the smallest of that type.

To string it requires a procedure that is not quite easy, as you have to overcome a very strong reflexity. The string has two symmetrical and very long loops, hanging loosely over the ends of the bow. Hook the one loop into the one nock and secure it with the right hand, holding it upwards to the right. Then you step with the whole length of your right leg between string and bow, put the under end of the bow over your left knee, press with the right leg against the reflexity, and pull with both hands forward until you get with the under loop down to the lower nock to insert it.

This method of stringing is of historic interest, as it is pictured on antique vases. Perhaps even the Bow of Ulysses had to be strung identically."

Peter Dekker:

A rare photograph of a Manchu archer stringing his bow with the so-called "step-in" method. The Manchu style composite bow is indeed one of the most difficult bows to string. This is because of its reflexed C-shape and the comparatively thick limbs, the long ears don't help bending when stringing. A bow may be 60 pounds when pulled with the string attached to the tips of the long ears, but when stringing you first need to pull it from knee to knee where the force is much greater. My friend Magén Klomp is the only one I know that can string an 80 pound Manchu bow with the step-in method, and he says it is much harder than stringing his 130 pound longbow. The shade of red his face takes when stringing it compared to his longbow adds credibility to his statement!

An animation of me stringing a Manchu bow with the method seen in the old photograph.

Courtesy of Duke Bhuphaibool.

14.) From a historical postcard of Qingdao, circa 1900. Photographer unknown.

Peter Dekker:

Clearly a staged picture, but a charming one at that. Take note of the following: The archer does not use the thumb draw common among expert archers of the region. His bow-arm and wrist in unnatural positions and he grips the bow too low, a common beginner's mistake. As for the equipment, I don't know who fletched that arrow but what we see here was not common practice for Chinese fletchers. And last but not least, the lower string bridge is missing so the bow is likely to unstring itself upon release.

Justin Ma:

Literally a poser.

15.) By William Charles White, Fuzhou, date unknown.

Peter Dekker:

This photograph is staged in order to show both archer and target at the same time. The man's stance seems pretty much classical Manchu with the slight difference that his bow rests in the palm of his hand instead of on the flesh between index finger and thumb. It is unclear whether this is a branch of Manchu archery or a mix of Manchu and Chinese style.

16.) By Adolf Erazmovich Boiarskii, Beijing, 1874. National Library of Brazil. The photograph was taken during a Russian trade mission into China that took place in 1874-75 and was lead by Lieutenant Colonel Iulian A. Sosnovskii.

Peter Dekker:

An archer in Beijing about to raise his bow to begin the draw. You can see that his body is turned in a 45 degrees angle towards the target he is gazing at. Beautiful image. It appears to be mirrored, judging from the clothing.

Comments, questions? Discuss Manchu archery in our Facebook group:

- - - Do you know of any more Manchu archery pictures not listed here? If so, DO let me know! - - -