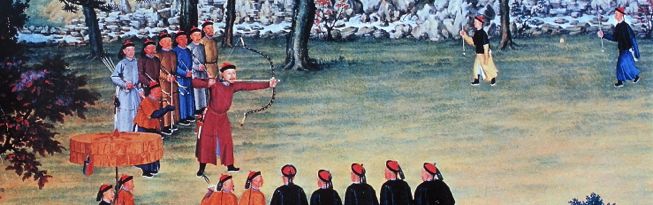

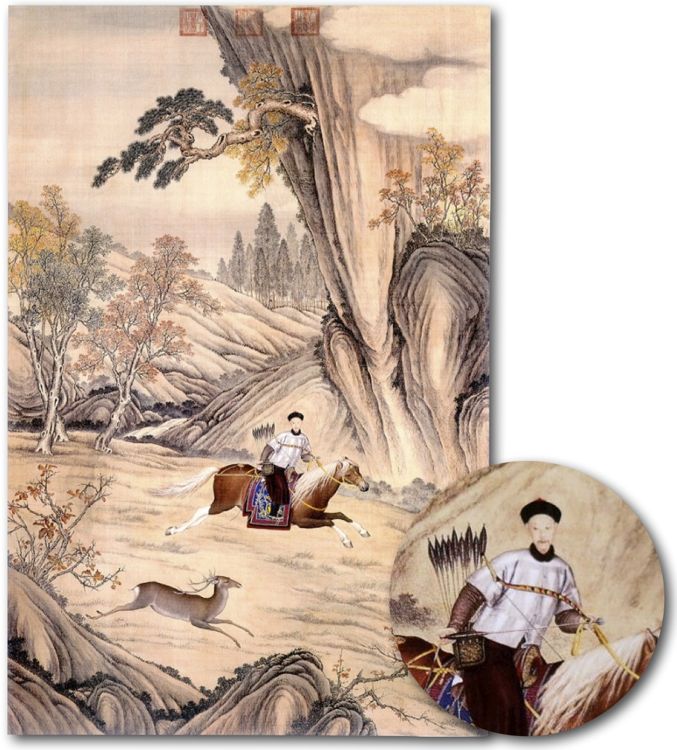

The Qianlong emperor showing his men how it's done.

By Peter Dekker, October 23, 2014

The Qing emperors of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were avid archers. But unlike the elites of Mughal India, the Ottoman empire, Persia, and others known for their lavishly decorated bows with lacquer and gold, imperial Manchu bows were often only modestly decorated with black paint on raw birch bark. They typically had exposed horn bellies and birch-bark covered backs, decorated with camouflage-like patterns, rather similar to their standard military bows. In fact, from a distance these bows looked exactly like the plain-looking, naturalistic designs of the bows carried by common officers and soldiers. Difference could only be seen up-close; imperial bows were made with the best quality horn, wood, sinew and birch bark available, crafted with the highest workmanship standards. While they may look plain to the untrained eye, the beauty of them is really in the little details.

The Qianlong emperor in full ceremonial armor. Literally everything is flashy except his bow; it is of plain naturalistic design adhering to Manchu instead of Chinese aesthetics.

A bow previously owned by the Kangxi emperor who reigned from 1662 to 1722. The imperial household tag dating from 1669 states that it is 7½ li, equivalent to 100 pounds. It shows the typical humble style of imperial bows of the period, similar to that of his grandson Qianlong, in the previous picture. This bow is currently held in the Palace Museum in Beijing.

When flamboyant decoration made it to bows

It was under the Qianlong emperor that the Chinese flamboyant decorative motiffs -that surrounded the Manchus since their conquest- also made it to their bows. He started to redesign a number of regulation pattern weapons, many of these new designs were set in 1748.1 Among them the Jianruiying "Cloud Ladder Saber". A key feature of the design was the incorporation of stylized cloud shapes on its fittings and the use of cutouts of the same designs as were later found in the birch-bark backs of bows. First princely, this design would later become standard on military bows and sabers of the imperial army.

A Qing military saber of the mid 19th century with stylized cloud-shaped cutouts in the brass scabbard fittings.

Author's collection.

Black bark patches with stylized cloud cutouts on the backs of two Chinese bows of the 19th century.

Author's collection.

More stylized cloud cutouts in the leather reinforcements of a Qing imperial bowcase and quiver set.

The gilt fittings also follow the outlines of stylized clouds.

Author's collection.

Why clouds?

A theory I'm having: The mandate of heaven rested on a Chinese emperor's shoulders only by grace of the support and belief of the people that the current house was fit to rule. The Qianlong emperor was very well aware of this fact and his own non-Chinese origins, was always looking for ways to attempt to legitimize Manchu rule over the Chinese people. Often, he would hark back to Han Chinese precedents.2 He may have incorporated these Chinese cloud designs into these weapons -overruling the traditional Manchu aesthetics with traditional Chinese ones- as a way of conveying that they did not just serve the Manchu ruling elite but that they executed the will of heaven itself; the clouds being a sign of heavenly continuity of the Chinese dynastic cycle. Even more, the imperial army was even respectfully called the "Heavenly Troops".

The Qianlong emperor was also actively designing and redesigning weapons for his personal use during this period. Also dating from 1748, we see the first depiction of a type of bow that was not of the standard, naturalistic Manchu design: Instead the back of its limbs appear to be covered with an elaborate geometric pattern. At least three of these bows survive, two and are currently in the Palace Museum in Beijing. One of them bears an inscription labeling it a 寶弓 (baogong), or "precious bow", as opposed to the regular 弓 (gong) or "bow" that we find on the imperial household department tags attached to the naturalistic looking bows in the Palace Museum. Bows that were owned and used by the various emperors, but apparently still did not classify as "precious bow".1 The inscription on this particular baogong further describes how the Qianlong emperor shot a deer with it near a river bank at the imperial hunting grounds in Mulan in, again, the year 1748.

The baogong with which Qianlong shot a deer in Mulan. Held in the Palace Museum collection, Beijing. Its main distinguishing features are the bark covering at the back with mosaic chevrons in the hollow of the knees and geometric patterns on the working sections of the limbs.

Baogong in artwork

Several pieces of artwork depict the Qianlong emperor with bows with limbs covered in similar geometric patterns as the baogong illustrated above.

A magnificent large hanging scroll of Qianlong checking the straightness of his arrow. By Giuseppe Castiglione. Although famous and widely published, none of the reproductions of this painting in literature quite reproduce it large enough in order to see the details of the bow. I took this picture during a very close encounter with this painting when it was on temporary exhibition in the Louvre in Paris.

Qianlong hunting deer with what appears to be a mosaic-patterned baogong.

Another painting of Qianlong hunting. It seems to be the same bow as depicted above.

Another painting of the Qianlong emperor out and about with this time a very delicately looking mosaic patterned baogong.

Antique baogong

I am currently aware of seven antique baogong with this kind of limb decoration. Two of them, both in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing, were published. The first is published in ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF THE QING, part 6; the Qianlong era (清史图典-第六册 -乾隆朝) Xinhua University Press, Beijing 2002, pp. 21. The second is published in DE VERBODEN STAD, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam 1990, pp. 238. Another example is in the Palace Museum in Shenyang, brought to my attention by Wen Chieh.

At least four baogong are in private hands. Two in a unanimous private collection in China. Unfortunately both specimen are in rather bad shape, with most of the bark decoration gone. Another, fine and complete example is in the collection of Mike Richard of the United States who kindly provided me pictures and measurements of his bow. The last example is mine, this one is remarkably close to the overall design and layout of the two published imperial bows, up to the swastikas on the inside of the knees.

THE BAOGONG OF THE SHENYANG PALACE MUSEUM

The bow in the Palace Museum of the old Manchu capital of Shenyang.

This is clearly a very early example of the type, judging from the still experimental style of decoration. For example, the portion near the handle with stylized waves is not seen on any other bow. The very understated transitions lines of the cartouche containing the longevity symbol are also quite unlike the later, more standardized work of bows of the 19th century. It is most likely dating from the 18th century and among the first of such bows.

THE BAOGONG OF MR. ZHOU

Currently in the collection of Mr. Zhou. I photographed this one in Beijing in 2006 at Yang Fuxi's workshop, before it went to its current owner.

A rather late type, probably made around the mid 19th century. A pretty bow in its time, with white horn bellies and mosaic patterns on the knees but not on the working limbs. It was delicate, probably of a rather light draw weight.

THE BAOGONG OF MIKE RICHARDS

A beautiful example of a mosaic-decorated baogong with intricate mosaic patterns of colored birch-bark. Note the similarity of the main pattern to that on the Shenyang museum example. It has ray-skin covered ears, high-quality translucent horn bellies showing paintings done on the core of the bow. Its lavish decoration is floral in theme with stylized longevity symbols disguised as vases with flowers. An exquisite piece of work in excellent condition. One ear bears a maker's mark, suggesting it was made somewhere after the 1860's.4

Measurements:

Ear tip to knee 29.2 cm (signature end) and 29.8 cm5

String nock to ear knee 24.8 cm (signature end) and 25.4 cm

Mid limb width 48 mm

Mid limb thickness 11 mm

Mid handle to knee 59.7 cm (signature end) and 59.7 cm

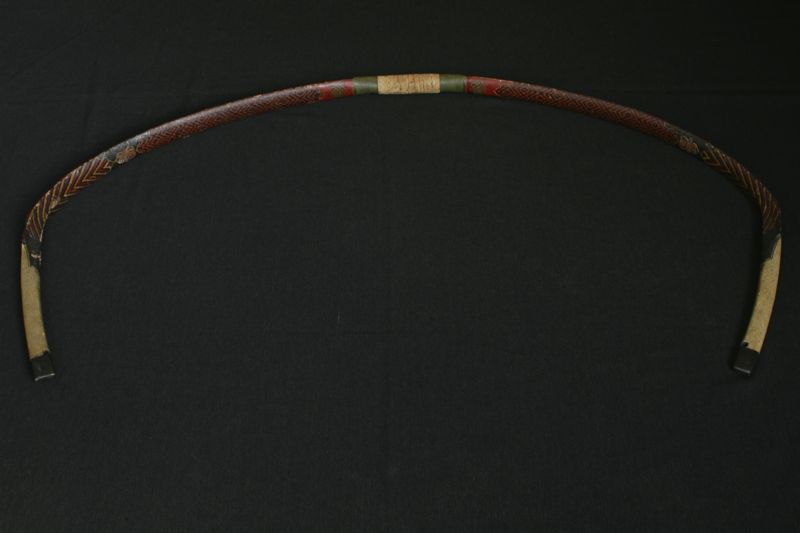

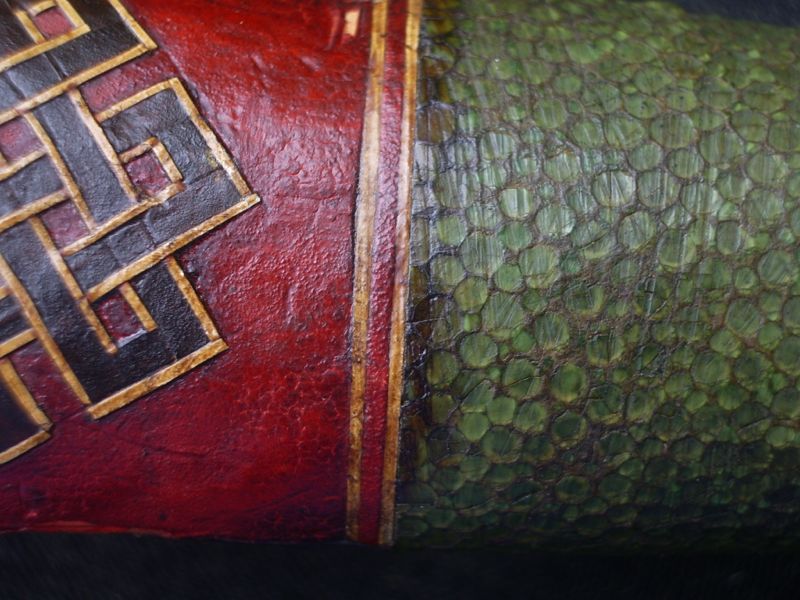

THE BAOGONG OF PETER DEKKER

My baogong is a somewhat earlier example, bearing close resemblance to the general layout of some of the earliest baogong used by the Qianlong emperor. One of the main differences with Qianlong's bows is that my example has ray-skin covered ears where the other published bows that are attributed to the Qianlong emperor have ears either covered with birch bark or plain wood colored red. According to the regulations ray-skin was used during the Qianlong period on military bows and bows of the imperial guard, but Qianlong doesn't seemed to have fancied this material for his own bows.4 The decoration of this bow combines the eternal knot with a gourd, a symbol for generating offspring while the double lozenges in the birch bark mosaic pattern represent military victory. Together they represent dynastic continuity through reproduction and military victories. Thus the decoration on this bow reflects the concerns of the Manchu ruling elite, rather than the more mundane wishes for fortune and happiness more commonly found on bows of the upper middle classes.

Measurements:

Ear tip to knee 28 cm and 29.5 cm5

String nock to ear knee 23 cm (signature end) and 24.5 cm

Mid limb width 38 mm

Mid limb thickness 13 mm

Mid handle to knees 63,5 cm

Weight 760 grams

Estimated draw weight between 60 and 70 pounds.

Another one of the Qianlong emperor's mosaic-patterned baogong, in the Palace Museum Collection, Beijing. Note the identical layout to the previous bow, up to the swastika on the inside of the knee.

The main difference is the absence of ray skin on the ear.

1See the weapon's sections of the 1759 皇朝禮器圖式 (Huangchao Liqi Tushi), chapters 14 and 15.

2See Elliot, Mark; EMPEROR QIANLONG, SON OF HEAVEN, MAN OF THE WORLD, Longman publishing group, 2001.

3For the inscribed baogong see 情史图典: 乾隆朝 (上) 紫禁城出版社, 北京, 2002. p. 21. A good number of the naturalistic bows are published in 故宫博物院藏文物珍品全集 56:请宫武备, 商务出版社, Hong Kong, 2008. (The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, Beijing 56: Armaments and Military Provisions).

4According to Stephen Selby such maker's marks were only done after the 1860's. Before that time makers had more subtle ways of branding, hidden in certain design features of the bow.

5Although they generally look symmetrical, Manchu bows are always slightly asymmetrical and they have a clear top and bottom part. Most bows have subtle differences in decoration to help the archer to distinguish top and bottom. Other bows bluntly have the characters "up" and "down" on each limb.

Also see: