By Peter Dekker, January 23, 2014

Introduction

This is the first part of the story of Ku Ku, who is probably the last Manchu archer alive. It is an expanded version of an article originally published in Journal of Chinese Martial Studies*. The magazine kindly granted permission for me to publish the article online as well. This first part will explain how we learned about her existence and present some family backgrounds, most notably about her father, Tong Zhongyi. The second part will cover the actual encounter and the interview, with photographs of that event.

*Journal of Chinese Martial Studies, Winter 2012. Issue 6. Three-In-One Press, Hong Kong. 2012.

Serendipity

Our encounter with Ku Ku, who may very well be the last formally trained Manchu archer alive, was serendipity at its best. It all started at the 3rd World Traditional Archery Festival in Busan, South Korea in 2010. We got into a conversation with Sheikh Fouad who runs traditional archery school Leap Programme in Kuala Lumpur. He told us that when he was in a Chinese bone-setting practice in Singapore, he spotted a black and white picture of a young lady shooting a large Chinese composite bow. As an archer himself, he enquired about the photograph and the bone-setter, Ku Ku, replied that it was herself in her younger years! She further told him she was a Manchu of a lineage that had been close to the imperial line, and had been taught archery by her father, who was an imperial guard and physician of the last emperor, Puyi. Amazing, I had not dared hope to ever find a living practitioner of the Manchu style, let alone one with such pedigree.

Left: Sheikh Fuad and myself in Istanbul. Right: The photograph on the wall of Ku Ku's old practice.

Illustrous forefathers

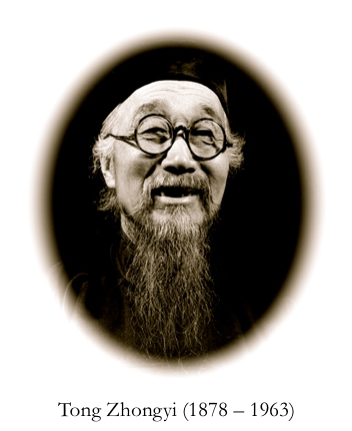

Ku Ku is the daughter of Tong Zhongyi (1878 – 1963), also known as Tong Lianchen, who according to Ku Ku was born under the Manchu Plain White Banner. Her grandfather was Tong Enrui, also an accomplished martial artist, and a bone-setter. Her great-grandfather Tong Mingkui was garrissoned at the frontiers of the Qing and gave his life defending them.

A court painting depicting a Qing army (right) chasing Muslim rebels (left) at the Western frontier in the late 19th century. These were the frontiers where Ku Ku's great-grandfather Tong Mingkui served and died. Painting sold at Sotheby's in 2013.

The Plain White Banner

All Manchus were born under one of eight "banners", gusa in Manchu. The banner affiliation determined the position in the field when called for action, and in case of the capital Manchu banner forces, it determined where they resided in the city and what part of the wall they were assigned to protect. In the Forbidden City the Plain White Banner was stationed between Dongzhimen and Chaoyangmen gates in the east of the walled "inner city" of Beijing and resided in the space between that section of the wall and the Palace in the west. Han Chinese were allowed to come here for trade, but were not allowed in these parts during the night. Together with the Plain Yellow Banner and the Bordered Yellow Banner the Plain White Banner was one of three banners that were under direct control of the Emperor himself where the other banners were (in principle) lead by princes.*

*For a thorough study on the Eight Banner system, see: Elliot, Mark C. - The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press; 2001.

Clan affiliation

Ku Ku did not know much about her earlier family, neither did she know their Manchu clan name. This was common, as most family histories were destroyed during the fall of the Qing as Manchu's tried to blend into the Chinese population out of fear of prosecution. I did some research on this lineage, and the White Banner turned out to be a great hint. I found out their family lineage can probably be traced back to the Tunggiya lineage of pre-conquest Jurchen who conquered the Pozhu valley. According to the “Collected Genealogies of the Eight-Banner and Manchu Lineages” the Tunggiya originated at Maca. Detailed maps of the Qianlong period show Maca as an easterly tributary of the Tunggiya-ula, or Tunggiya river from which they derive their name. What distinguishes them from the other Manchus who took a Tong surname is that the Tunggiya were all registered under the Plain White Banners -like Tong Zhongyi- while most of the other Jurchen that ended up with Tong surnames were registered under other banners like the Plain Blue Banner. The Tungiya clan, who later adopted the Tong surname, were part of the Jianzhou Jurchen that were to initiate the conquest of China under lead of Nurhaci. So although not an imperial lineage, they were very closely interwoven with the dynasty and many Tong’s served close to the royal house. In the end of the seventeenth century it was even said that the Tong’s filled up half the court (“tong banchou”) referring to the many civil and military officials in high ranks that bore the Tong surname.*

*See: Arthur W. Hummel - Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, University of Michigan Library, 1943.

Tong Zhongyi

Tong Zhongyi lived up to the reputation of his forefathers: Trained in martial arts and bone-setting by his father, made quite a reputation in his home town. Together with Wang Zi Ping they were referred to as: "The two masters of Changzhou". He expanded his repertoire by learning wrestling from the Mongolian bannerman Tsai Ging Tien, his father's oldest disciple.

A rare old photograph of the young Tong Zhongyi demonstrating the long spear.

At 17, Tong Zhongyi moved to his uncle who owned a private security company. He served as a caravan bodyguard in 1899 (the 28th year of the Guanxu emperor) and subsequently joined the army where he worked his way up to become a military police official at age 30. He subsequently worked as an instructor for the Imperial Guards under the Xuantong emperor, whom we know simply as Puyi. After the fall of the dynasty he was employed as a bone-setting physician for the elite Chahar province (present-day Mongolia) cavalry and in the 6th year of the republic, 1918, he became a wrestling instructor for the Anhui Third Army. Later he became wrestling instructor for the Four Provinces’ combined security forces, captain of the Wuqiao protection group, chief instructor of the Zhili (Hebei) Infantry Military Academy and ultimately became head of the Shaolin division of the Shanghai Municipal Martial Arts Academy. He is author of "ZHONGGUO SHUI JIAO FA” or The Method of Chinese Wrestling, first published in 1935. The book is still important for students of martial arts today, presenting a unique view into wrestling and its traditional training methods through clear text and many photographs of Tong Zhongyi and his students.

Tong Zhongyi was one of the few late masters to have learned a complete system of martial arts. As is the case with many other horse-riding people such as the Mongols and many traditional Islamic cultures, wrestling was the unarmed foundation of the Manchu martial curriculum. Tong Zhongyi was also an excellent horseman and mounted archer, infantry archer, heavy bow puller, and remained unbeaten even with the pellet bow. The story goes that people could challenge Tong Zhongyi on the following disciplines:

1) Pole-shaking: whoever shook the pole the most times was considered the winner;

2) Drawing a bow: whoever could fully draw a 100-pound bow the most times was considered the winner;

3) Flicking pellets: whoever could hit bronze cymbals suspended from a tree at a distance of 30m the most times with 30 pellets won; and

4) Shuai Jiao: whoever could beat him 2 times out of 3 bouts would be considered the winner.

Apparently, no challenger ever managed to beat him at these aspects! Read more about him in the online article Tong Zhongyi and his Shuai Jiao. When Tong Zhongyi passed away he was granted a "level two" state funeral for his accomplishments in the realm of martial arts.

As a major figure in Chinese martial arts at the time, Tong Zhongyi was also involved in the organization of several martial arts or "guoshu" tournaments. In the above picture he is seen, third from the right, as one of the referees of the 1st National Tournament of 1956.

A series of photographs of Tong Zhongyi at practice taken by Jack Birns of Time magazine in 1947 when he was 69.

Ku Ku

Ku Ku is known in China under the name Tong Peiyun 佟佩雲. She was Tong Zhongyi's eldest and was trained by her father in archery, wrestling, and various other martial arts including Six Harmonies Boxing. The family system was called Tong Pai Ji Ji Shu or "Tong family combat techniques school" In 1948 Ku Ku won the women's wrestling division of the Shanghai City Sports Event, and in 1957 she won gold in archery on the 30 meter competition with her Manchu composite bow in the last tournament of its kind. I met and interviewed Ku Ku in Januari 2012. This interview will be subject of part II of this article.

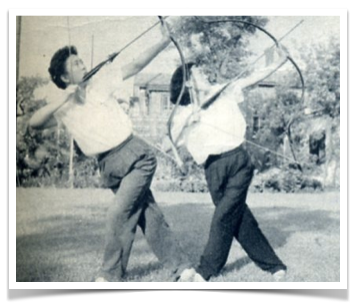

The young Ku Ku practicing wrestling with her father in 1947.

Ku Ku shooting the Manchu composite bow with her sister.

The photograph that got us in touch! Ku Ku winning gold in at the last traditional archery tournament in 1957.

Part 2 coming soon!

FURTHER READING:

Hummel, Arthur W. - Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period, University of Michigan Library, 1943.

Kennedy, Brian and Guo, Elizabeth Nai-Jia - Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals, Blue Snake Books, Berkeley, California, 2005.

Tong Zhongyi - The Method of Chinese Wrestling, North Atlantic Books, Berkely, California, 2005. (Translation of the 1935 original)

CONTINUE TO PART II ...