By Peter Dekker, April 7, 2014

Introduction

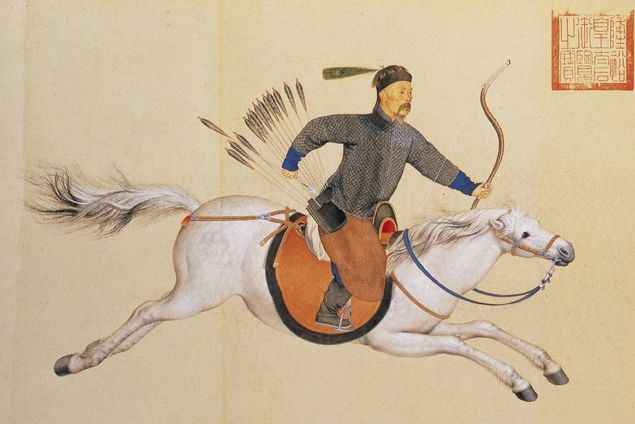

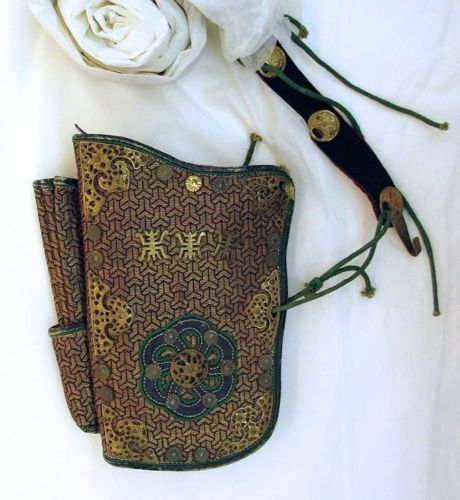

Like most Asian armies, the archers of the Qing suspended their bow case and quiver from a belt that also carried their saber. There was quite some overlap in the overall style of bow cases and quivers from Korea to the far East, all the way to the Ottoman empire to the West, but the sizes, material and decorative patterns differed from culture to culture. The bow case of the Qing dynasty is a cloth or leather "holster" that covers only the bottom half of the bow, leaving the grip exposed so it could be drawn out efficiently. The open quivers used by the Qing army are rather short in relation to the arrows, leaving most of the shafts of the arrows exposed and spread out like a fan, so they can easily be picked out one by one. Although some elements like the material of fittings for certain ranks were more or less stipulated by regulation, we see a great variety of materials, styles, and decorative patterns used, reflecting the personal tastes of soldiers who were often given a monthly fee in silver to purchase and maintain their own equipment.

Among antiques, the higher grade bow cases and quivers are now rather over-represented because those were the ones that were taken from China as war trophies or purchased by early collectors, while most of the simpler equipment made for soldiers was lost over time because hardly anybody thought about keeping them for later generations. As a result, I've been able to examine and photograph far more bow cases and quivers of high ranked Qing officers, mainly the imperial guard, than I have of soldiers. However, the general construction of bow cases and quiver of the Qing is the same, difference is mostly in materials and decoration.

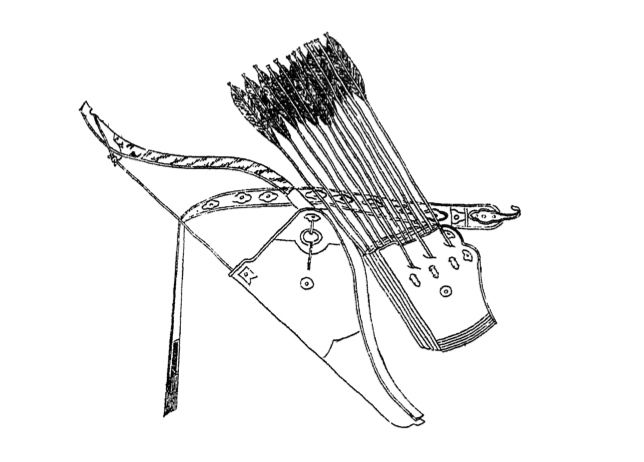

An archery set for the regular soldier from a 1899 edition of the Da Qing Huidian Tu or "Illustrated Statutes of the Great Qing". It reproduces a 1759 manuscript commissioned by the Qianlong emperor (ruled 1736-1796), and represents the style of that period.

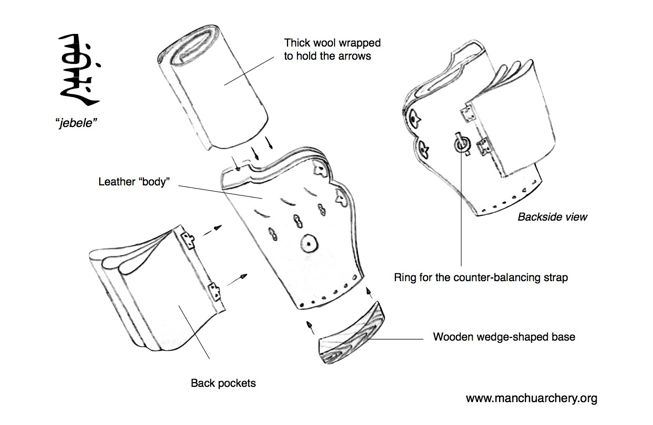

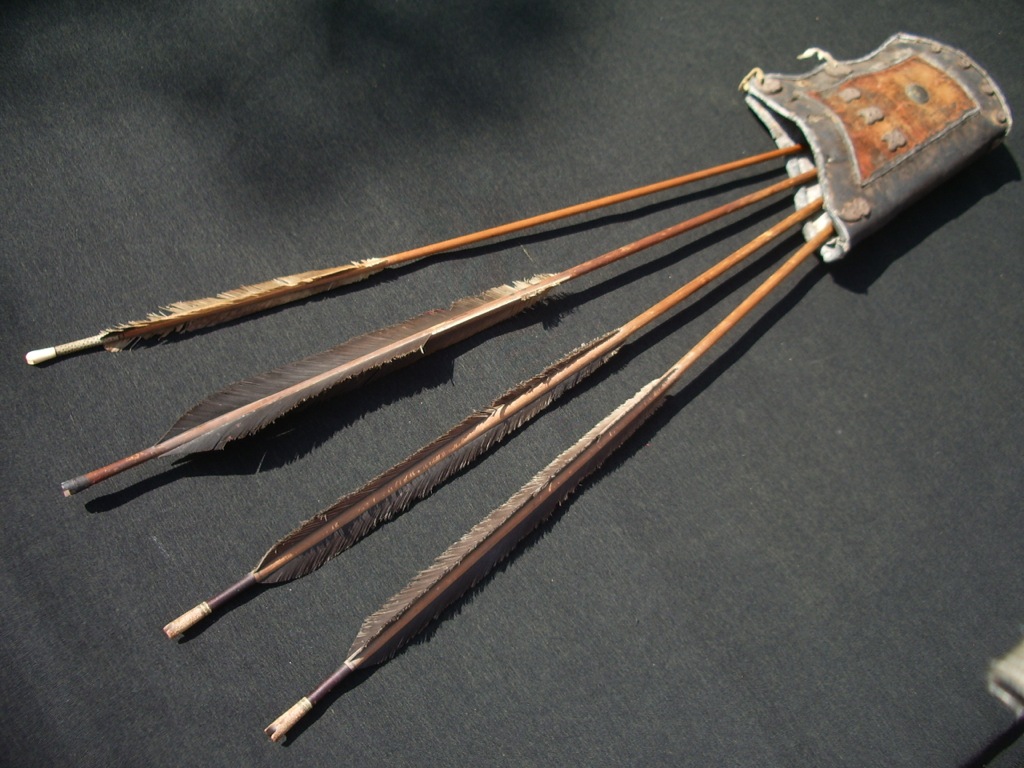

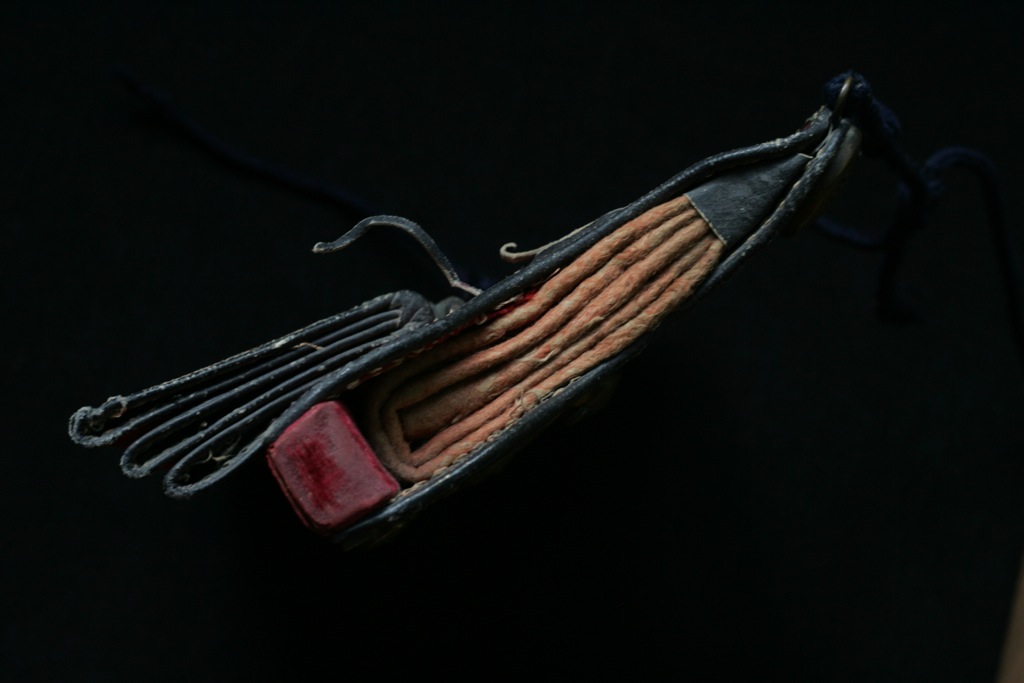

The Manchu quiver is called jebele in Manchu, which simply means "right hand" or "right hand side", indicating just how deeply archery was engrained in their culture. The Chinese term for this type of quiver is 撒袋 (sā dài) which means "spreading bag", named after the manner in which the quiver spreads the arrows out. It is typically made with a wooden base with leather or rawhide folded around it. The leather may or may not be covered with fabric, such as velvet. The arrows are held in place between thick fabric, often wool, and one or two fasteners that go through the top of the quiver to tighten the whole. Some of these are threaded, with wing nuts, to squeeze the arrows tightly in place. Quivers of the first half of the Qing would also often have three slits cut in the front for extra arrows or otherwise have a double front, the outer part covering the bottom half of the from of the quiver, to put at least two extra arrows in. Quiver fittings can be made of simple brass sheet or forged iron, to cast brass or pierced iron work which was gilt for the higher ranks.

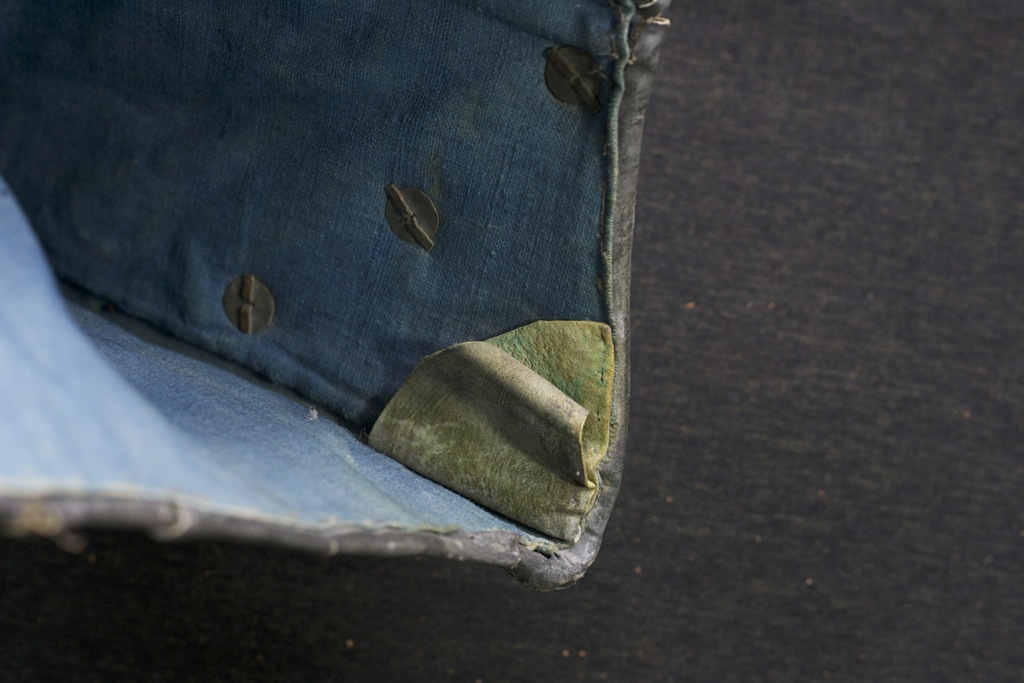

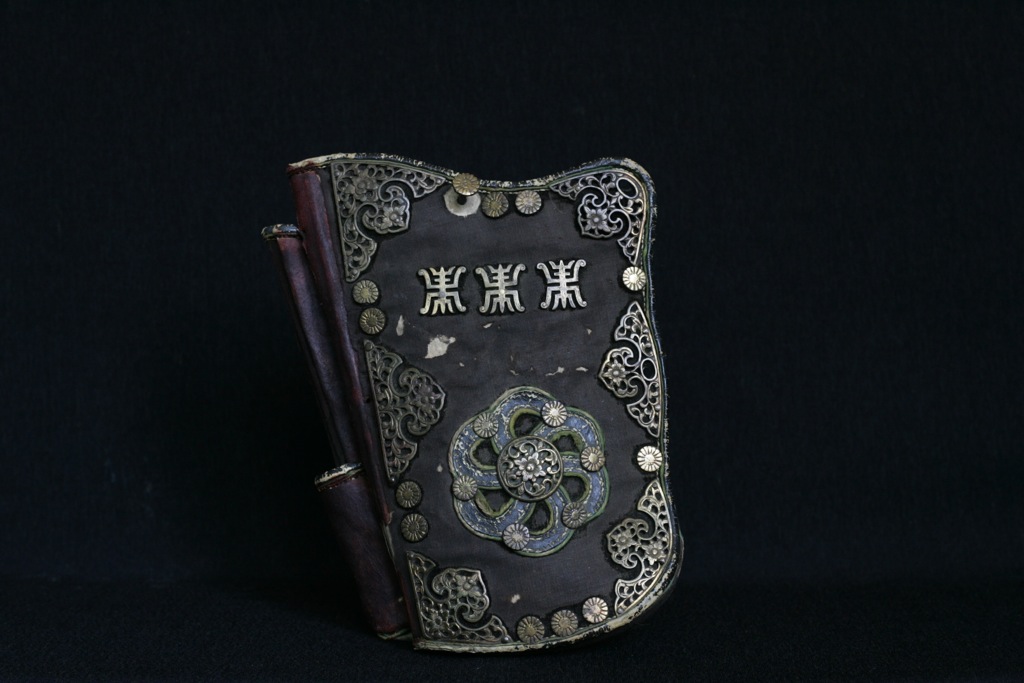

A quiver belonging to the imperial guard of the late 19th century. Once covered with black velvet, most of that is gone now. On the front are three stylized longevity symbols. Inside cushion missing. Sold through Mandarin Mansion. Anonymous private collection.

Extra pockets

Manchu quivers always have a number of flexible pockets attached to their backs with two or three metal hinges. Many antique quivers have lost these back pockets but the holes where the hinges were can still be seen. The pockets are made so they can expand to hold some of the many special arrows the Manchus had with larger heads such as whistling arrows, blunts, or other specialized arrows. There are almost always three such pockets, although I've seen rare examples with two or up to four pockets.

A quiver that belonged to the Qianlong emperor. He wore this set while performing the tri-annual Grand Review of the Troops in Beijing. Notice the felt inner cushions and the three soft pockets on the right. Palace Museum, Beijing.

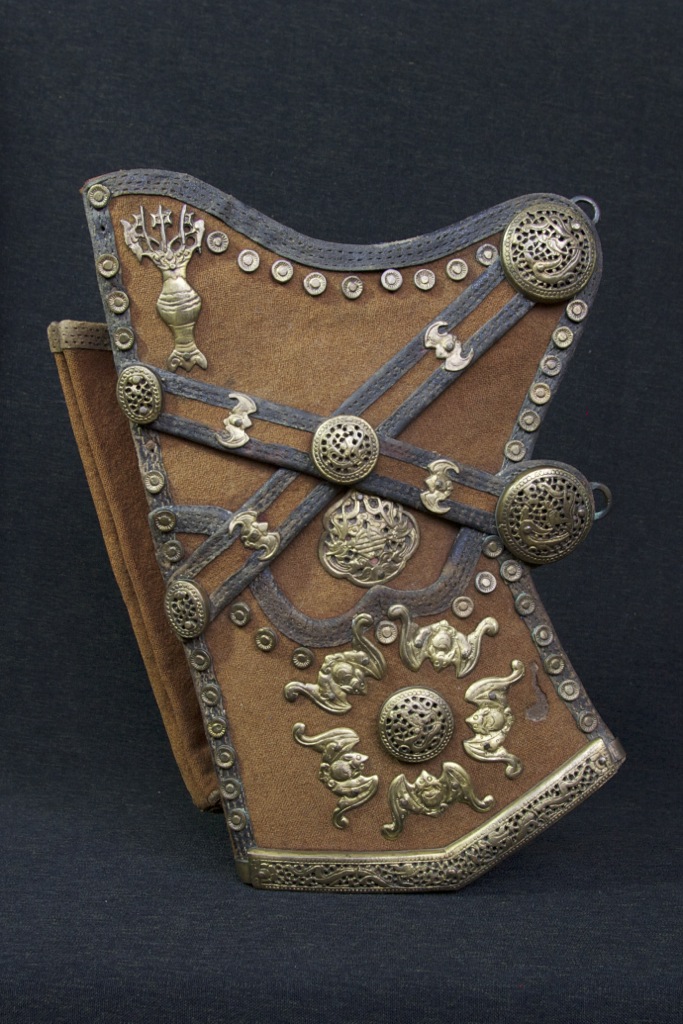

A quiver belonging to the imperial guard of the early 19th century. Usually these come only in red or black, worn in different occasions. This particular example was once a maroon red velvet, a color I had not seen before. Otherwise it exactly follows the patterns of the other examples in various museum and private collections. From my own collection.

Manchu officer Badai and his quiver. The quiver represents the standard quiver model in use in the mid 18th century, the height of the Qing's military power. Note the three slits in the front and the three pockets on the back that were common for this era. Painting held in the Asian Art Museum of Berlin. Badai was honored for breaking enemy lines single handedly. According to the poem accompanying the scroll, he fell from his horse, hastily dressed his wounds and continued shooting: "Many were felled as he snapped the string of his bow".

Quiver suspension

Manchu quivers are suspended from two rings on the right side of the quiver, and one or two straps to counter balance them on the back. These counter balancing straps are very important because a full Manchu quiver would otherwise topple from the weight of the arrows. Like with the pockets, many old quivers have lost these points, but the holes where they were attached can still be seen.

A set of bow case, quiver and belt in the Charles E. Grayson collection. This type of bow case and quiver would have been worn by the imperial guard of the late 19th century. The bow case is suspended from a fittings that can slide over the belt. Also note the extra straps on the back to counterbalance the quiver. Photo courtesy of Jonathan Stephanoff.

Quiver contents

Qing soldiers could choose to fill their quivers with either standard military arrows or military broadheads. The broadheads do more damage but have a more limited effective range while the standard military arrows had more penetrating power and flew further. Because Manchu arrows are rather large and heavy, they never carried many of them. My own quiver weighs exactly 2 kilo when I fill it to it's maximum capacity of 16 arrows. A typical quiver contained anywhere from 9 to 19 arrows as far as I've been able to determine, the regulation pattern quivers of the imperial guard carried exactly 13 arrows when they rode out to accompany the emperor on longer journeys: 5 military arrows called "plum needle", 5 broadheads, and in their three special pockets a hare fork arrow, a whistle arrow and a whistling arrow). This may not seem like a lot, but Manchus never seemed to have went for the hails of arrows one regularly sees in movies. Instead, the Qing mounted archers singled their targets out and went after them on horseback, shooting concentrated shots at moderate "sure" distances, just like they did during the hunt.

My own quiver full of arrows, 16 in this case. It's a replica I got from Magén who runs Fairbow.

Officer Machang pulling an arrow from his Manchu quiver. This quiver has a double back with space for two extra arrows. This is a portion from the painting "Machang lays low the enemy ranks" where Machang is depicted chasing an enemy soldier, killing him with three arrows. Painting by Giuseppe Castiglione, ink on silk, 1759. Painting held in the National Palace Museum of Taipei.

Dashūwan in Manchu, means the left side, opposite of jebele for quiver. The bow cases are of elegantly simple design; cut out of leather or rawhide, sometimes covered with fabric like velvet, or made of fabric alone with leather patches at the corners and bottom to strengthen the whole. They are folded on the string side while the other side is sown together with a separate piece between it that can expand to accommodate the width of the bow. A unique feature of the Manchu bow case is a ring, often oval in shape, that is designed to hold the bare saber. It is called the dashūwan i muheren in Manchu. Manchu cavalry are sometimes seen carrying the saber in this way right before commencing a battle. Advantages of this setup are that the saber is easy to pull, and a base saber hanging down from the bow case would also discourage infantry to try to pull the rider down from it.

Two antique bow cases, recently sold through Mandarin Mansion. Left: Imperial guard black velvet and leather quiver. Black velvet bow cases and quivers were by regulation worn by the imperial guard during sacrificial ceremonies and court assemblies. Right: Exquisite dark brown velvet and leather bow case of a high ranked officer of the 18th century, with fine gilt fittings.

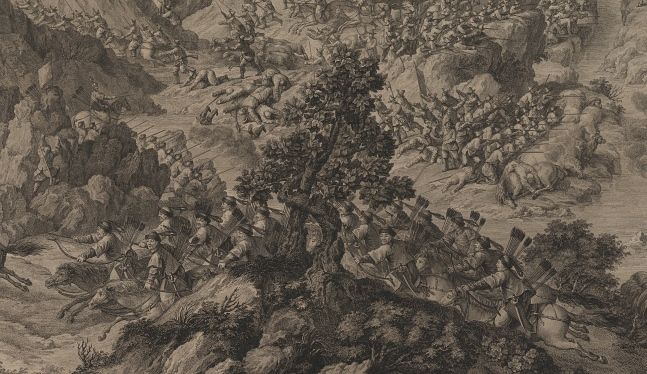

Detail of the copperplate engraving print of the battle of Yesil-köl-nor, that took place in September 1759. On this occasion, ten thousand Qing soldiers met an equally large force of Muslim Turkmen, capturing 2000 of them and killing many. It shows a group Manchu soldiers riding into battle with their sabers through the rings on their bow cases.

Standard configuration with the saber worn hilt backwards. It could be drawn quickly from behind the back, as was observed by Father Martino Martini in the 17th century. Another method of drawing was to move the hilt forward and draw the weapon edge up for a downward cut.

Battle configuration. This may have been used when meelee combat was likely to occur. Perhaps similar to the order "affix bajonets" among armies of gunners today.

The archer's belt, aksargan.

Bow case and quiver are suspended from a special belt made of leather, or leather covered with fabric. A commonly encountered form of such a belt consists of a piece of leather between two layers of fabric, often silk on the outside and cotton or linen on the inside. The fittings are peened with pins that go through the outer layer and the leather. Most belts close with a hook on the right side that goes into one of three loops on the left side. On the right side there are three to four loops to which the quiver straps are attached. These loops may all be on separate fittings, or one of them may be attached to the underside of the hook. The two loops closest to the hook side attach to the two loops on the right side of the quiver. The one or two additional loops attach to one or two rings on the back of the quiver to counterbalance it when full of arrows. On the left side of the belt is usually only one fitting to hold the bow case. On some belts, this fitting is made so it can slide over the belt to change position, on others it is fixed.

An 18th century archer's belt from my own collection. The thick brass fittings are engraved with eternal knots, with some of the original gold remaining. The outer belt is of thick woven silk, with a leather inner belt and cotton or linen lining.

Regulations for bow cases and quivers, at least as far as the metal parts concerned, were rather similar to those of the fittings on their sabers. According to the regulations, ordinary soldiers were only allowed to have unadorned brass fittings on their bow case, quiver, belt and saber. Low ranked officers could have engraved brass fittings. In practice, iron fittings are also encountered. Only the higher officers had the right to wear fittings with gold or silver, with entirely gilt metal being reserved for the highest ranks. In the early days, the metal was usually gilt iron, later gilt copper or brass became the norm. Certain styles or combinations of materials were reserved for the imperial guard, who had several sets to fit a number of occasions ranging from attending auspicious ceremonies to escorting the emperor on longer tours outside the capital. Various semi-precious stones and some types of fabric were preserved for princely ranks, and only the emperor himself could wear fittings studded with the so called "Eastern pearls", large freshwater pearls from the Manchurian rivers, but he only wore those on certain occasions like the tri-annual Grand Review of the Troops in Beijing. Not everything the emperor had was flashy though, on some occasions he was promoting the old and simple ways of their frugal Manchu ancestors, in which he gave the right example by carrying a simple leather bow case and quiver with bare iron mounts. Apart from regulation pattern bow cases and quivers, we see a large variety of non-regulation pattern equipment that range from the simple and practical to the flamboyant.

A bow case and quiver for the princely ranks of qinwang and junwang, originally titles for uncles, nephews and brothers of the emperor, but on occasion also bestowed to men for exceptional service to the Qing. The "mountain pattern" silk brocade covering of the quiver matches that of their ceremonial armor. See the whole suit plus bow case at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, U.S.A..

A bow case and quiver set that belonged to the Qianlong emperor, worn at the Grand Review of the Troops in Beijing. Palace Museum, Beijing.

A 19th century quiver with simple but well-made iron fittings. Unfortunately the back pockets went lost, along with the rings for the counter balancing straps on the back. Currently owned by Wen Chieh Huang.

A quiver sold on auction at Hermann Historica. It is of general Manchu design but the decoration reminds strongly of Mongolian work, suggesting it was perhaps used by one of the many Mongolian bannermen serving the Qing. Especially studded leather and the hook shaped fitting on the upper left of the quiver are indicative of Mongolian design.

A Buryat Mongolian quiver from the Ingo Simon collection, now housed in the Manchester Archery Collection in the Manchester Museum. Often mistaken for Manchu quivers, but they are narrower and rounder and always made of leather.

A quiver part of a set of a red velvet bow case and quiver, belonging to an imperial guard officer of the 19th century. The red color was worn by the imperial guard when escorting the emperor to the Yuanmingyuan and back, when clearing the streets for an imperial procession, and several other occasions. Recently sold through Mandarin Mansion

I hope you enjoyed this article! If there are any questions, let me know and I might expand upon this. Also, if you have any bow cases or quivers to share, I'd love to see the pictures.

More about archery equipment: